SFA's first Black professor is honored with an endowed memorial scholarship established by former students

Story by Parastoo Nikravesh '18 & '23

This past September, as the summer heat began to fade, Lumberjacks came together to celebrate SFA's centennial. Thousands of Lumberjack memories poured in during the months leading up to the Sept. 18 birthday bash, all reflecting on the formative time the university played in their lives.

While waxing nostalgic during this moment of celebration and reflection, some alumni stories became a humbling reminder that not everyone experienced equal access to the collegiate experience throughout those 100 years.

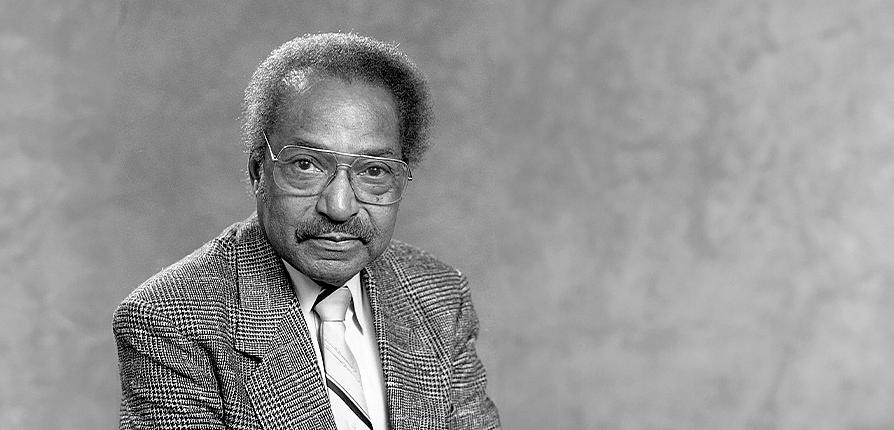

In fact, it's been only 55 years since SFA welcomed its first Black professor to the front of the classroom. The late Dr. Odis Rhodes joined SFA as a professor of reading and language arts in 1968 and made history during his more than 20-year tenure at SFA, leaving an indelible mark that will be remembered for years to come.

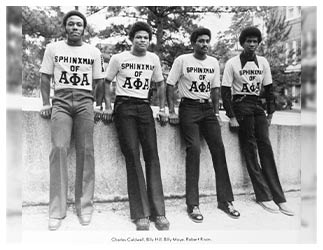

While a professor at SFA, Rhodes also was a faculty advisor for the Alpha Phi Alpha Iota Mu fraternity. To honor his tenacious pursuit of education and celebrate the centennial in a unique way, fraternity brothers established a memorial scholarship in his name. The Dr. Odis Rhodes Memorial Scholarship was officially endowed in September 2023 and will be awarded to an SFA student in fall 2025.

Creation of this scholarship offered a unique opportunity to reflect on the legacy Rhodes left behind and his place in SFA's 100-year story.

Winters Hill

Rhodes' interest in education began in childhood. He was born in a rural farming community 11 miles northwest of Nacogdoches called Winters Hill that, at the time of his birth in 1931, consisted of 10 to 20 African American families. His grandfather had a farm of approximately 200 acres, making him one of the few African Americans at the time to own a sizable tract of real estate to farm his own land.

Rhodes was interviewed in 2012 — three years before his passing — by SFA graduate students Jake Keeling and Tracy Allen for inclusion in the SFA East Texas Research Center's East Texas African American Oral Histories project.

During the interview, Rhodes described how the families of other adjoining farms were close-knit and often helped each other. He also mentioned the work was hard — it included pulling corn, digging potatoes, chopping cotton, and planting and picking cotton.

Rhodes knew it wasn't the job he wanted to do for the rest of his life. However, career options were sparse for Black people at the time, and Rhodes' teachers discouraged his aspirations of becoming a lawyer.

"They just saw no future in becoming a lawyer for a little poor Black boy in Lufkin, Texas," Rhodes said. "They'd say, 'It's best to be a teacher or a barber.'"

When asked what inspired him to go into higher education, Rhodes put it simply: "Cotton patch. I hated the cotton field, and I said, 'If there's anything else in the world I can do for a living to get me out of this cotton patch, I want to do it.' And, as I said, [teaching was] about the only opportunity that was open to me … so I went into teaching. Then I fell in love with learning."

Unfortunately, there were obstacles to Rhodes' pursuit of education and to the aspirations of other children in the Winters Hill community, which had a school that included only first through sixth grades. The predominantly white community of Douglass three miles away had a school that went through the 12th grade, but it was segregated. This left Winters Hill children to bus 15 miles away to Nacogdoches' E.J. Campbell High School.

"[Kids in the Winters Hill area] kind of looked forward to get out of sixth grade because we went to town to school at E.J. Campbell in Nacogdoches; but, of course, we would have preferred to simply go to Douglass, which was just right up the road," Rhodes recalled.

Rhodes stayed in Winters Hill until the seventh grade when his family moved to Lufkin. He graduated from Dunbar High School in 1950.

Besides distance, the poor condition of books and materials was another obstacle to Black students' education. Rhodes recalled not seeing his first new book until the 1940s when he was in the 10th grade. Books before then were passed down from the white schools and were often missing pages.

"So, you talk about Blacks being behind educationally," Rhodes said. "We've been pushed behind and chained behind and held behind for generations. So how in the heck can you expect a person to be at the same level when you held them back, giving them discarded information?"

The call to higher education

Despite living in Lufkin, Rhodes could not attend the then-segregated SFA, and in 1954, enrolled at Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, earning his bachelor's degree in biology and physical education.

He held a variety of teaching and administrative positions in public Texas schools in Waskom and Lufkin. Rhodes later pursued graduate degrees at Texas Southern University and the University of Houston, earning master's and doctoral degrees, respectively, before moving back home.

Although he had gained exceptional qualifications, his career advancement opportunities were thwarted by lingering intolerance upon his return to Lufkin. Luckily, a significant social shift was happening just up the road, enabling him to land an interview at SFA.

Under SFA President Ralph W. Steen, Rhodes was hired in 1968 as the first African American professor at SFA — and would remain the only one for six years.

He described his first few years as uneasy at times, but he eventually felt accepted by most on campus.

"And one thing [university administrators] didn't do, they didn't make a big pronouncement or announcement like 'Stephen F. Austin hires first Black professor.' They just quietly eased me in under the radar, and I think that helped," Rhodes said.

While some students were surprised and a few dropped Rhodes' class due to his race, he found after time he had garnered a good reputation among the students.

"Dr. Odis Rhodes was one of the finest individuals I have ever known," Dr. Thomas D. Franks, retired professor and dean of SFA's College of Education, said in a 2015 story in The Daily Sentinel. "[He] showed everyone who had the privilege to know him how to overcome adversities in a variety of forms in pursuit of worthy life goals," Franks said.

Franks first met Rhodes in the fall of 1967 when Rhodes interviewed for a teaching position at SFA. They worked together for 24 years until Rhodes' retirement in the winter of 1992.

"No one was respected, admired and loved by colleagues and students more than Dr. Rhodes," Franks said. "No students complained about how he treated them. Instead, they rated him highly as a professor and expressed appreciation for the manner in which he related to them."

In 1996, Rhodes was named professor emeritus of elementary education, becoming the first Black professor to receive that recognition at SFA.

Alpha Phi Alpha

In addition to his teaching role, Rhodes was the faculty advisor of Alpha Phi Alpha Iota Mu chapter, where he made an incredible impact on many young Black men who attended SFA.

One former student, Vince B. Adams '88, helped organize Rhodes' memorial scholarship. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in business administration and management and was a recipient of a full-ride scholarship for football. Adams met Rhodes when he was initiated in Alpha Phi Alpha in spring 1985.

Adams recalled how Rhodes was affectionately referred to as "Doc" by the men in the fraternity and said Rhodes looked after the brothers and emphasized their academic excellence. To the Alpha Phi Alpha men, Rhodes was an example of hard work and resilience.

"He was dedicated to African Americans, in particular African American males, getting their education, and that's why he was in higher ed," Adams said. "But still, being one of the only African American professors, he probably had a lot of challenges with that. Knowing how he transcended all of that to become the man that he was is inspiring."

Adams has carried Rhodes' experiences with him for many years, describing Rhodes' educational background as one of the main motivations for him and his fraternity brothers in establishing the scholarship.

The social and historical gravity of Rhodes being barred from attending SFA due to segregation then becoming its first Black professor was "major," Adams said. "We don't fully understand the plight people like him went through, but it's very humbling. I want younger generations to understand that. There isn't any excuse to not succeed academically. You just have to want to."

Honoring his legacy

After Rhodes passed away, Adams said several of the Alpha Phi Alpha men agreed to do something to honor his memory. That's when conversations of a memorial scholarship began.

Adams praised the support of Daron Deckard '87, another Alpha Phi Alpha brother who helped organize this scholarship, as well as Dr. Alton Frailey '83 & '85, former member of SFA's board of regents. Ultimately, the Alpha Phi Alpha brothers raised $29,830 — more than the original goal of $25,000.

"I thank God for the tenacity of the ones who gave," Adams said. "There were a lot of people who gave that weren't even members of the fraternity, like [Rhodes'] family. Even his former church in Lufkin, First Mission Baptist Church, donated. So, people who knew his legacy contributed to the cause."

Adams hopes those who receive the scholarship look up Rhodes' history and learn about the type of man he was — and ultimately pay it forward, challenging other alumni to make a difference for students.

"We got what we wanted, and to God be all the glory," Adams said. "We can make a difference in some kids' lives who attend our beloved Stephen F. Austin State University."

Axe ’Em, Jacks!

Axe ’Em, Jacks!