An Anthropologist and An Archivist Study Enslavement Histories — and Are Expanding Our Understanding of the Past

Story by Christine Broussard '10 & '20

Illustration by Emily Kubisch '17

Photos by Trey Cartwright '04, '06 & '12 and Robin Johnson '99 & '19

When Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, a recorded 182,566 enslaved people lived and labored on Texas soil.

Despite not being told they were free until two years later when Gen. Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston on June 19, 1865 (celebrated today as Juneteenth), the proclamation meant millions of formerly enslaved people could now build new lives for themselves as free U.S. citizens.

In a legal sense, millions of humans considered mere property, at the scratch of a pen, suddenly became free people — but of course that was not their reality. The truth is generations of enslaved people had names, hopes, dreams and desires, and they led complex and often brutal lives. So how do we tell their stories — those of diverse people silenced by slavery?

It's arduous, meticulous work that requires picking through probate, deed and mortgage records; poring over runaway slave ads; sifting through soil; and charting moon and star alignments.

Thankfully, one SFA alumna and one SFA archivist have separately taken on, in their distinct fields, the backbreaking work of combing through sources to uncover the realities of a vast people whose daily lives and contributions have been largely forgotten to history.

Anthropologist Dr. Rolonda Teal '18 and archivist Kyle Ainsworth are by no means the only people digging into Texas' enslavement history. But they're making great strides in the pursuit of telling these often long-forgotten stories.

African Diaspora in the South

Teal built her career at the cross-section of multiple disciplines — she received a bachelor's degree in anthropology from Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana; a master's degree in historical archaeology from the University of Houston; and a doctoral degree in forestry with an emphasis in human dimensions from SFA in 2018.

Teal has been researching the African diaspora and migratory pathways of fugitive people in Texas and Louisiana for more than a decade — much of it springing from a singular paper she wrote during her master's program on the Cane River Insurrection of 1804.

This event saw a mass escape attempt of enslaved people from Natchitoches Parish, the magnitude of which "points to the ability of community to provide the framework for large-scale attempts at freedom and resistance against servitude," according to the Cane River National Heritage Area website.

"I always knew I wanted to study African-American history because I felt it was missing, so my research centers on the African diaspora, plantation systems and fugitives," Teal said. "My 1804 paper from that one history class continued to develop and develop, branching off in different directions. So, I have worked on this story for over a decade."

With assistance from other archaeologists, ethnographers, GIS specialists and the like, Teal has discovered and published conclusive evidence that there was significant movement of enslaved people traveling south to Spanish-owned Mexico in 19th-century Texas, including along the famous El Camino Real de los Tejas.

This discovery of southerly escape routes is touched upon only slightly in existing scholarship because many claim the primary source support just isn't there.

Teal disagrees, saying it only requires putting in time, effort and a bit of ingenuity.

"Jeffrey Williams, who works the GIS component in SFA's forestry and geospatial science program, was able to reconstruct the timeline of the 1804 escape," Teal said. "He used his knowledge of horses and how far someone could have ridden them in a certain amount of time, and we mapped a trail from the plantations over to the Sabine River. We could actually trace a timeline for where they should have been at certain times and where they were when they got caught. He could also tell me it was a full moon on Oct. 16, 1804, which fit the descriptions of that day that I found in primary documents."

Digging through both Spanish and French primary source records, she's uncovered stories of how and why slaves rejected servitude. Her aim is simple: to ask new questions and seek out new information to build on existing knowledge.

"We have histories of which we've been taught for years and years, and we're understanding more how these histories are not complete, so my goal is to add to and expand the narrative," Teal said.

This fact is one historians increasingly acknowledge.

"It is crucial to understand that history is revisionism. That's the whole point — the past is not static," said Dr. Court Carney, professor in SFA's Department of History. "Not simply in a metaphysical way (the idea that the past continues to change), but in a concrete way. We simply know more about the past than we did a generation ago.

"The work of scholars like Ainsworth and Teal is a good example. Their work deepens and complicates established ideas. A complicated narrative reflects a complicated story. We know our present-day lives are complex knots of knowing and unknowing. The same was true for people in the past."

Teal's goal of narrative expansion has, at times, been met with indignation from academic peers who feel her work is calling established history into question. When she's approached with skepticism, Teal finds comfort in the objectivity of her research.

"Natchitoches Parish: American is woven of many strands..."

Written by Dr. Rolonda D. Teal

"What I've learned is I don't have to argue with them about it," Teal said. "I just say, 'Here's my stuff. Until you can put something together that contradicts it, I'm going to keep asking tough questions and researching new stories.'"

The decades Teal has invested in researching the African diaspora has led to the inclusion of three Louisiana historical sites in the National Underground Railroad Network of Freedom. She also works often, and closely, with the National Park Service and various state park services for all manner of research, from archaeological and ethnographic studies at federal construction sites to training national park interpreter staff members on implicit biases.

Teal has also appeared as a guest on the Discovery+ docuseries "Underground Railroad: The Secret History" and, for fans of all things spooky, an early episode of "Ghost Adventures" as they paid a visit to Magnolia Plantation in Natchitoches.

The Project of a Lifetime

Texas Runaway Slave Project

As an archivist and special collections librarian in SFA's East Texas Research Center — and with master's degrees in history and library science — Ainsworth's daily life is a continual trek through the winding aisles of SFA's archival stacks.

Ten years ago, with easy access to the extensive primary sources kept in Steen Library's ETRC on the SFA campus, he began a bold project: collecting, transcribing, organizing and cataloging the thousands of runaway slave ads published in Texas newspapers throughout the early 19th century.

"The focus of my master's work at the University of Southern Mississippi was slavery and Reconstruction, and I needed a research project to fulfill the scholarship component of my faculty status at SFA, so I saw a great opportunity to investigate a subject that already interested me," Ainsworth said. "I also evaluated the accessibility of Texas newspapers (the main source of runaway slave records) and saw that I was uniquely positioned to do the research."

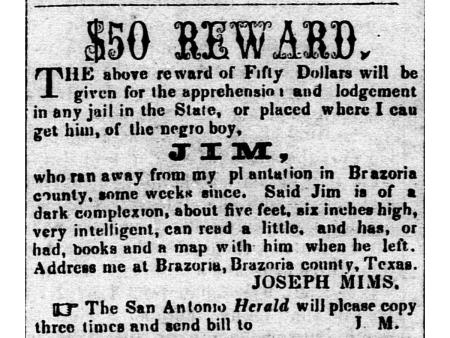

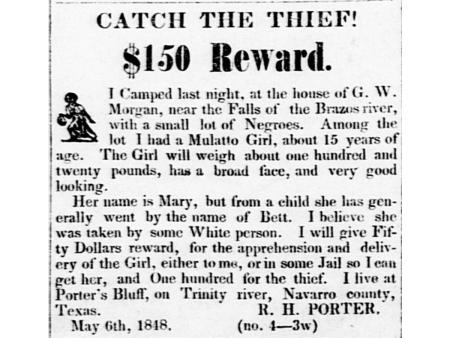

The Texas Runaway Slave Project started in 2012. Over the next two years, Ainsworth reviewed 3,100 newspaper issues, scouring for ads placed by slave owners seeking help to find their runaway slaves. These types of ads are unique in the annals of enslavement, and deeply paradoxical: as one of few documents that described individual slaves in detail — albeit from the perspective of their enslaver — the ads juxtaposed rare glimpses of enslaved people against stark reminders of their place as commodities in Texas' 19th-century economy.

Photo caption: Two examples of the thousands of runaway slave ads published in Texas newspapers throughout the early 19th century

"Kyle's work gives us an incomparable view of slavery and freedom seeking in Texas," said Dr. Alice L. Baumgartner, an assistant professor in the University of Southern California's Department of History who used the TRSP while researching her first book, "South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War." "This database is the main reason we're seeing a boom in scholarship on enslaved people escaping to Mexico … and the Texas Runaway Slave Project allows anyone with an internet connection to get a sense of how important this escape route was."

Fast forward a decade, and the TRSP has now reviewed nearly 20,000 newspapers from 1835 to 1865 and has identified more than 2,500 individual runaway slaves from Texas.

"Kyle's work is a tremendous resource for scholars and students of Texas because he has created a purposeful archive that not only has collected so many runaway slave ads, but also connects them — and the people named in them — in ways that only someone as close to the records as Kyle has been could possibly do," said Dr. Andrew J. Torget, University Distinguished Teaching Professor in University of North Texas' Department of History. "That means the TRSP does more than just make records available — it brings together the people embedded in those records and recovers their stories in ways that offer a new window into the Texas past."

Lone Star Slavery Project

Ainsworth's search for runaway slave ads churned up mounds of deed, probate and other official records that mentioned the movement of slaves between owners and among properties.

These documents weren't relevant to his runaway slave research, but he didn't want them to remain unused.

"One of the things that always bothered me when I was doing the runaway slave research was that I was finding lots of other stuff about slavery but having to let that fall by the wayside," Ainsworth said. "At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when SFA suspended many on-campus operations, I stayed in the archives researching and photographing Nacogdoches deed and probate records. That's when I started the Lone Star Slavery Project."

Though only two years old, the LSSP seeks to flip the script for how people investigate slavery in Texas. Without the enslaver's name, finding documents on enslaved people is nearly impossible because county records and archival collections are organized by the name of the enslaver. By cross-referencing all records, Ainsworth is able to follow the stories of individual slaves as they move through the historical record and organize the LSSP database by the enslaved person's name.

The project's ultimate goal? To archive, county by county, every reference of every enslaved person in Texas mentioned on paper.

The work has barely begun and is something Ainsworth sees "as a lifetime project. I approach it how I approach the runaway slave project, which is incrementally. If I think about 180,000-plus names, it would just be too much. Last year I worked on Nacogdoches County. This year is another county. It's something that can always be added to."

As Ainsworth chips away at archiving the whole of Texas' slave history, each addition to the projects' database is another piece laid in the vast mosaic of enslavement stories. It's also an outlet for historians, sociologists, archaeologists and genealogists to pull from as they seek to uncover more of the state's past.

"Historical scholarship rests on archival work. Historians and archivists form a symbiotic relationship based on the analysis of source material, and good archives are the products of good archivists," Carney said. "These repositories offer the building blocks of scholarship in innumerable ways, and having someone like Kyle is doubly helpful because he has a solid understanding of the historical profession in various ways."

Donate to further ETRC research

The Impact

Ripping at the undergrowth that had for years slowly crept over soil and stone, Rodney Hawkins and members of his family — alongside SFA history Professor Dr. Perky Beisel, her students and other volunteers — toiled in the fall of 2020 to unearth the two-century-old Old Mount Gillion Cemetery headstone by headstone.

A producer for CBS News at the time, Hawkins was on assignment covering a story that was very personal to him and members of his family. Their intentions for the project started simply enough: with generations of Hawkins' ancestors buried in the Nacogdoches County cemetery, he and his family wanted to learn a bit about their past while restoring what they could in the present.

Just six months later, Hawkins' ancestral quest took an emotional turn — using names and dates found on the recovered headstones, Ainsworth dove into the LSSP database and emerged with records showing the movement and sale of Hawkins' great-great-great-grandfather, Richard Curl.

Moments like these are examples of the magnitude that research like Teal's and Ainsworth's can have on present-day lives.

"That was an amazing moment of realization and connection for me," Hawkins said. "I knew I had roots in East Texas, but I didn't have a clue where, how and who began our legacy here. I felt connected to this country, Texas and my family in ways that are hard to explain. Despite the circumstances, Richard Curl made a life for himself after slavery, and I wouldn't exist without him. To have the opportunity to present this information to my living elders was priceless. As my great uncle Billy Curl said, 'I have a history now.'"

Slavery research impacts much more than just scholarship. It connects whole families and uncovers truths that can impact entire communities.

Take, for example, Teal's research on the El Camino Real de los Tejas route. She discovered that in the tiny community of Geneva, a historical marker identifying it as a stop along El Camino Real was originally placed along Kings Road, which cut through the small town's Black community. The marker was moved, however, a couple miles over to Highway 21, not only disconnecting the town's Black community from its historical significance but also stripping it of the chance to receive grant funding to build its identity as a historic place.

Enslavement research not only provides a historical basis for financial support but also allows people and communities to truly get to know themselves. And while trying to tell the story of all those people suddenly freed from servitude is a bold pursuit, Teal's and Ainsworth's work creates real change. Because connecting people and communities to their past does more than simply tell a story — it impacts how we understand and support those people and communities in the present.

Axe ’Em, Jacks!

Axe ’Em, Jacks!