Conservationist and Olympian oversees efforts to save endangered grouse

Story by Sarah Fuller '08 & '13

Photos by Hardy Meredith '81

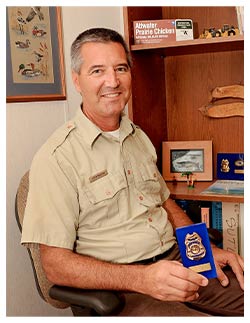

Class of 1992

A dense fog engulfed the early spring morning as John Magera '92 led a group of visitors to a clearing on the Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge. Stepping out of the vehicle, the group stood in silence as the distinct, whirring calls of the critically endangered Attwater's prairie chicken filled the air. The birds' vocalizations, coupled with the rapid thumping of their feet and vibrant, inflated air sacs on each side of their neck, are part of a unique courtship display, known as booming, performed by males in an effort to attract a mate.

"I've led a lot of tours, but that one really sticks with me," Magera, the refuge's manager, said. "This group of 15 male birds was just booming their heads off. They were probably a quarter mile away, but it was just a continual resonance. You couldn't tell where one prairie chicken stopped and the next picked up."

Considering the species' narrow escape from extinction, this annual performance is a literal celebration of life thanks to the dogged efforts of biologists who have dedicated their careers to ensuring its survival.

The refuge, located just a short drive west of the Houston metroplex, houses one of the last vestiges of Texas' untouched coastal prairie that the Attwater's prairie chicken and a host of native flora and fauna depend on for survival. Magera, who graduated from SFA with a Bachelor of Science in Forestry, has dedicated the past 12 years of his life to protecting this more than 10,000-acre stretch of coastal prairie and its inhabitants.

Magera has always loved the outdoors. As an SFA student, he was a member of the timbersports team, the Sylvans, where he was involved in archery events during annual Southern Forestry Conclaves. This participation would later help lead to his becoming a member of the 2004 Summer Olympic U.S. archery team in Athens, Greece.

Although working to save endangered species and becoming a member of an Olympic team might, on the surface, seem worlds apart, they both require tenacity and vision.

"I give credit to my forestry education for being able to maintain optimism while working to save the prairie chicken from extinction, because we were told straight away that this is a long-term process — you're going to be planting trees that you're never going to harvest," Magera said. "That really set me up well for this kind of work, because when you engage in the recovery of an endangered species, you're not working for results that you're going to see right away. You may have tremendous setbacks, but that's all part of it."

Once numbering in the millions across the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coast, rapid conversion of coastal prairie to agricultural use brought about by European settlement struck a substantial blow to the species' population, resulting in the implementation of state-mandated conservation measures as early as 1897. The introduction of non-native, invasive species, such as the red imported fire ant, also was extremely detrimental to its survival.

Natural factors, such as predation by raptors, skunks and coyotes, as well as severe weather events like hurricanes and floods, also contribute to annual dips in the birds' population.

By 1967, the Attwater's prairie chicken, which Magera quickly clarifies is a grouse species and not a chicken, was listed as endangered with a population of fewer than 1,000 birds.

Magera explained that the bird is a member of the ‘Class of 1967,' the original list of endangered species developed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that received federal protection under the 1967 Endangered Species Preservation Act — a precursor to the Endangered Species Act of 1973. The Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge is one of 60 national wildlife refuges across the U.S. established with the explicit goal of protecting endangered species.

Each year biologists introduce 100 to 200 Attwater's prairie chickens to acclimation pens located throughout the refuge, as well as on private ranches near Goliad. The birds, part of a captive breeding program established in 1993, are banded, and hens are fitted with radio telemetry devices allowing biologists to monitor future nesting sites. After two weeks of adjusting to the new surroundings, the doors are opened, and the birds begin their new life on the prairie.

The Attwater's prairie chicken is not the only endangered species Magera has worked to protect during his decades-long career with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. During his tenure at New Mexico's Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge, his focus centered on a number of endangered desert fish and invertebrates that rely on the refuge's wetlands. While these species may not receive the same fanfare of other more charismatic endangered species, such as the Florida panther or whooping crane, in Magera's eyes, they are no less deserving of protection.

"People would ask me what good is this or that particular species," Magera said. "My response is if you believe God created this animal, then who are we as human beings to cause it to become extinct?"

Magera's spiritual connection to nature is obvious as he gazes over the prairie, stopping to point out each instance a bobwhite quail, white-tailed hawk, black-tailed jackrabbit or distinctive feature of undisturbed coastal prairie crosses his path.

"How can you look at that and not see the hand of God?" Magera asked, motioning to the landscape of native flowers and grasses swaying in the breeze.

It was years earlier, while Magera was the refuge manager at the Middle Mississippi National Wildlife Refuge in Illinois, that he was reintroduced to his passion for archery. Magera enrolled his two oldest children in a local Junior Olympic Archer program. Curious to learn more, he once again picked up his own bow and arrow.

Possessing an innate talent, which he attributes to years of bow hunting in his youth, Magera decided to pursue Honorary U.S. Archery Team qualifying events during his free time.

Magera said he assured his wife, Karin '90 & '93, that he would not spend much money pursuing these events, and if he didn't do well, he would simply return to his hobby of shooting targets at home.

Among 78 archers participating in the first qualifying tournament, Magera found himself in second place behind the No. 1-ranked target archer in the U.S.

Several events and an Olympic trial later, Magera qualified for and became a member of the 28th Olympiad's U.S. Men's Archery Team that finished just shy of a bronze medal.

Following the Olympics, Magera was one of four coaches of the Junior Dream Team of teenage archers at the Olympic Training Center. In 2007, he was the assistant head coach for the U.S. Archery Team at the Turkish Archery Federation's Grand Prix event in Antalya, Turkey. In 2008, he turned down an offer by Kisik Lee, the national head coach of the U.S. Olympic Archery training program, to serve as the training center coach for resident athletes.

"I was flattered, and I told him that if I were much younger and didn't already have the career I dreamed of as a child, I would take him up on it," he said.

Accompanying Magera's dream job and his professional and athletic achievements is the very personal conviction that introducing youth to the natural world is absolutely imperative, not only for their health, but for the future health of the natural world.

"I get pretty passionate about projects that are going to get the next generation of kids into the outdoors and give them the opportunity to spend time in nature the way I needed to as a kid," Magera said. "I'll see kids riding their bikes or walking the trails, and I wonder if that is a future refuge manager. I wonder if that kid is going to consider a career in conservation."

Top image: More than a century ago, up to 1 million Attwater’s prairie chickens graced the coastal prairies of Texas and Louisiana. Each spring, males gather to perform a courtship ritual. They inflate their yellow air sacs and emit a strange booming sound across a sea of grasses.

Photo by John Magera

Axe ’Em, Jacks!

Axe ’Em, Jacks!