NACOGDOCHES, Texas — A group of researchers from Stephen F. Austin State University published a paper in the journal Animals that highlights how reintroduced noises related to human activity during the COVID-19 lockdown affected bottlenose dolphin attention and distractibility.

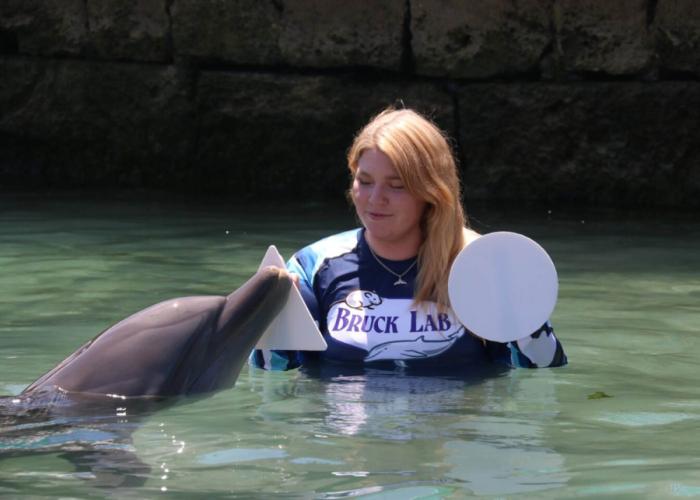

The paper was co-authored by Dr. Jason Bruck, research lead and assistant professor of biology at SFA; Paige Stevens, a doctoral candidate working with Bruck Lab; and Veda Allen, a graduate from SFA’s Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture. This research is being presented at the annual Animal Behavior Society Meeting in Portland, Oregon.

“The COVID-19 pandemic created a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that allowed us, as scientists, to peek at how these animals’ behaviors might change in the absence of humans,” Stevens said.

The paper, titled “A Quieter Ocean: Experimentally Derived Differences in Attentive Responses of Tursiops truncatus to Anthropogenic Noise Playbacks Before and During the COVID-19-Related Anthropause,” looked at how dolphins under professional care housed in a sea-side lagoon habitat at Dolphin Quest Bermuda responded to human-made sound from an underwater speaker.

Before the pandemic, the team exposed dolphins to safe levels of noises from cruise ships, jet skis and low frequency sonar. As a graduate student, Stevens collected behavioral data when the tourism industry was in its most restricted months during the pandemic. She compared these responses to pre-pandemic responses, allowing the team to see how dolphins paid attention to common sounds both under normal conditions and after months of greatly reduced ocean noise.

Under pre-pandemic conditions, dolphins paid less attention to familiar cruise ship noises than idling jet skis and sonar sounds. Once human-related noises resumed, the dolphins in the study increased attentive responses to all sounds but noticeably responded up to six times more specifically to cruise ship noise. The observation indicated that the dolphins would need to adjust to human activity once again.

“Cruise ships were really affected during the pandemic and had to stop operating,” Bruck said. “It seemed that before cruises stopped, the dolphins had habituated to the noises the ships made. After cruises started back up, we were surprised to see that the dolphins had lost their ability to ignore those sounds.”

Research like this helps those who work with aquatic mammals understand how they respond and pay attention to changes in noise pollution after extended periods of reduced human activity.

“This study helps us make predictions about how wild dolphins may struggle to avoid distractions in an increasingly noisy ocean when there are big changes in soundscapes,” Bruck said. “This research has implications for dolphin conservation in the Gulf of Mexico, especially in Galveston Bay, where all three of these noise sources may affect a resident population of dolphins.”

While distracting these dolphins under professional care holds no risk and causes no harm, animals in the wild may fare differently. Distracting a dolphin in nature may lead to ship strikes, failed hunts and lost calves, according to Bruck.

“For many, the obvious management solution to noise pollution and human activity is to decrease it,” Stevens said. “But what we see here is that the pattern may matter just as much as the type of noise itself. This study highlights that we must think not only about the effects of each type of noise but also about how we integrate ourselves back into areas after a long-term reduction of our activities.”

To learn more about aquatic biology at SFA, visit sfasu.edu/biology.

Axe ’Em, Jacks!

Axe ’Em, Jacks!