The Rusk Library: A model for the time

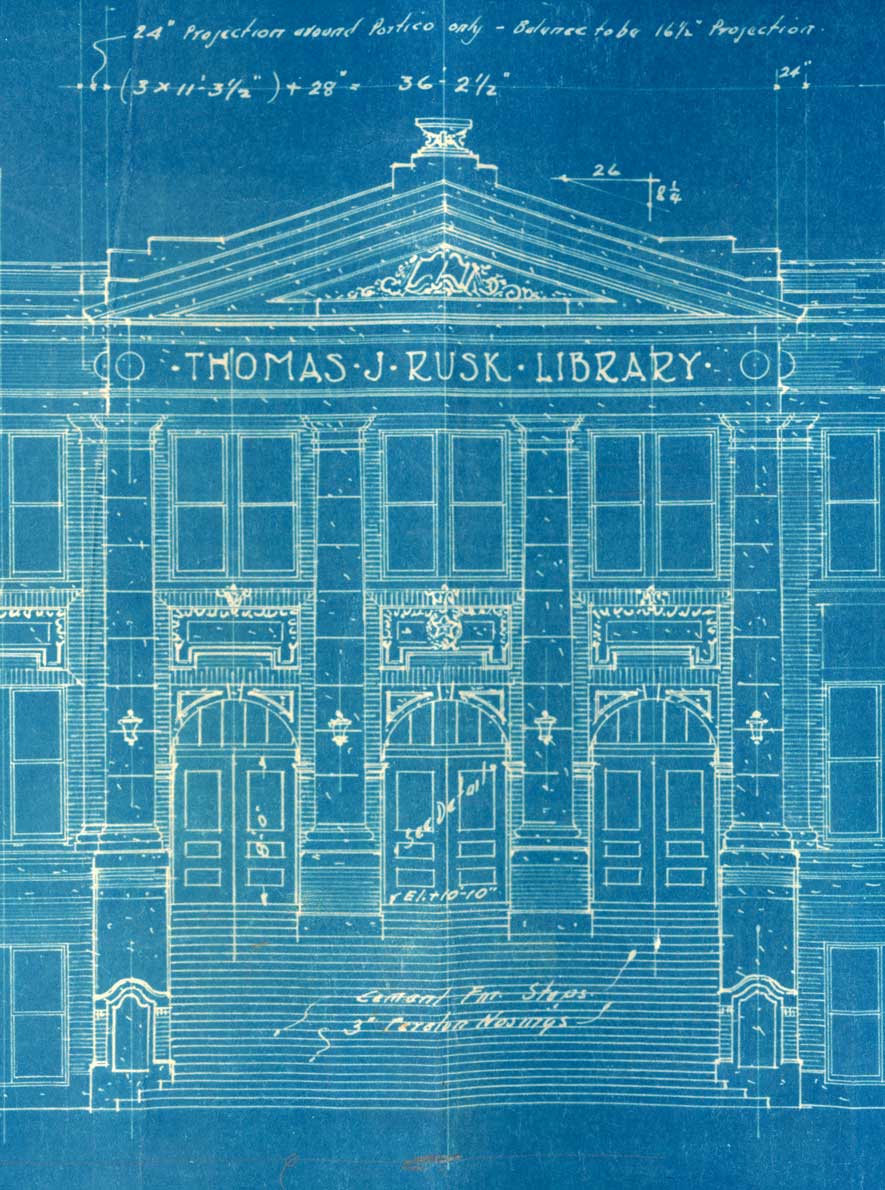

As one can see from the blueprints, the original intention for the Rusk Building was to call it the "Thomas J. Rusk Library." The tradition in almost every college at the time was to have "a main building" and "a library." There is every indication that this was the original plan for Stephen F. Austin from the time it was projected in 1917. There is an early hand drawn map in the archive showing the basic layout of the campus, before the drawing of a vista, which shows the main road and two buildings. There is a large X through the Rusk Building. This map has the date 1924, but it is impossible to know whether the drawing was projected into the date or was drawn in that year. When SFA moved into the Austin Building, the library there had a reference room of only 26 feet by 36 feet, a reading room 26 feet by 46 feet, and an office 9 feet by 26 feet.

The blueprint for the new second building drawn in the spring of 1925 designated it as the Rusk Library. It was not conceived, however, exclusively or solely as a library. As refined, the plan called for a library on the top floor housed in an education building along with classrooms and office. The architect designed a floor plan which pleased librarians at the time and was even touted as a model for library design of its kind. It was a good illustration of the "single floor layout," according to Library Quarterly where the design was written up for others to emulate. The plan made the most of its possibilities, according to the article.

"By placing the stacks, workrooms, and offices in the central portion of the floor, the two reading rooms have windows on three sides. A realization of the reserve book problem and its importance is evidenced by the delegation of one reading room for this branch of the work, with stacks for reserve books directly back of the charging desk in that room. The general charging desk is in the corridor in front of the stack room, and while artificially lighted, does eliminate that confusion and congestion for the reference room. The workrooms are conveniently near the librarian's office, the stacks, and the card catalogue, which is found in the corridor adjacent to the charging desk. A library-science classroom with an entrance from the reference room means easy transferal of reference books and tools for the instructor's use during class, and an entrance from the corridor allows the students to enter without disturbing any readers in the reference room. Unfortunately , the training-school library is on this floor, but near a stairway, so that the children need not even cross a corridor used by the college students. All desks are placed at points best suited for supervision and easy checking of books as students leave the reading rooms."

In a report shortly after it was opened, Miss Loulein Harris, the Head Librarian, stated that it was relatively free from outside disturbances, that the library rooms were not used for other purposes, that it was relatively fire proof (except for the wooden doors), and that the seating space exceeded accepted standards at the time. The one reservation she had was the reading room for the Demonstration School being on the same floor as the main library, but at least the children had access which did not require them to go through other rooms.

The Rusk Library collection was made up of the following distribution of books in 1927. The entire collection consisted of 7077 books and a pamphlet collection of another 2452. The value of the collection as of Jan 16, 1926 were listed a $14,101.00. The largest number of books were in geography, history and biography (1899). The next largest volume were in education and sociology (1469), followed by literature (1335). The fine arts had only about half the number of literature (760) and the sciences were on the bottom (501) of the academic areas. The general reference and library science books numbered only 230. In the professional categories, the highest volumne were on teaching methods and discipline, education history, theory, and principles; less promiment but also represented were curriculum, elementary education and psychology. Surprisingly, there were no books at all on secondary education and few on home education or the education of women.

While there are no records for the 1922-23 year, in 1923-24, 115 books were donated and 3685 were purchased for a total of 3800. This increased by another 1800 in 1924-25 and 2877 in 1925-26; because of the expenses of the move, less were purchase in 1926-27 (1707).

The Demonstration School had a library of 2,000 books, with 378 square feet of space and room for 26 students. The books followed the same general pattern as did the main library, with the largest single group in the history, geography, and biography categories.

The entire Rusk Library budget for 1926 and 1927 was $12,925.78. Salaries amounted to $4,800.00. Furniture for 1927, not including shelving and equipment charged as part of the building, was budgeted at $3, 632.15, and book purchases including freight totaled $3,284.18; with miscellanesous expenses, supplies, printing, subscriptions, student help, freight, etc. adding up to $2,209.45. The state appropriations covered only $8,600.00 of the budget and the other four or more thousand having to come out of local funds or adjustments from other departments in the college. The head Librarian made $200 a month, with the main assistant receiving $150 and a second assistant $100. There were allotments for six student assistants; they recieved $.25 an hour and worked approximately 20 hours a week.

While it depends on which document one consults, the Rusk Building cost approximately $218,025.54 and contained 11,000 square feet of space. The Library equipment and furniture cost an additional $3,374.50. By comparison, the Steen Library when it opened in 1973 cost $4.5 million and contained 145,000 square feet of space.