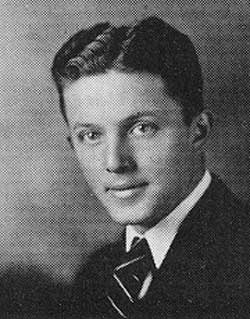

Victor B. Fain: Portrait of a Pine Log editor

During the year 1935-1936, the editor of The Pine Log was a young Nacogdoches County man named Victory B. Fain. Fain’s lifetime of distinguished newspaper work for the good of SFA, Nacogdoches, Texas, and the nation, is well documented. When he received the SFA Distinguished Alumnus Award in 1970, the university surveyed his service in the Navy during World War II, his professional career in the newspaper business, his many awards and offices, and his extensive public service and work with key boards in Nacogdoches. In a very public way, Victor’s career as the editor and publisher of The Daily Sentinel and the Redland Herald from 1946 until the time of his retirement in ____, is a matter of record. The purpose of this article is to look into his work in 1935 and 1936 to see what interesting facts we can add to what we already know about Victor Fain.

Fain, the son of a pioneer East Texas family, was born on May 14, 1915, in the North Church community in Nacogdoches County. He graduated from Nacogdoches High School and entered SFA in the fall of 1932 at the height of the Depression. There are no annuals for the years 1933 and 1932, so it is hard to follow his early SFA career; perhaps deeper research will reveal that in the future.

Victor makes his debut into the SFA print media in 1935 as the Pine Log Sport’s Editor. One of the editors at the time, Don Langston, categorized the Pine Log as “a number of cigarette ads connected by an occasional new story concerning happenings on the campus.” Sports reporting was certainly the other dominant element in the campus paper besides the ads. He quickly gained among other editors a reputation as a very self-assured commentator. Fain read and fed the student body’s insatiable appetite for the weekly ups and downs of the sports arena . These were heady years, however, with Coach Shelton producing championship basketball team after team. Winning teams are interesting and popular to cover, and Victor did his job well. In fact, he earned the title on campus as “the dean of East Texas sports writers,” according to one source.

Victor carried his knowledge of sports over into his work as Men’s Sports Editor for The Stone Fort in 1935. His pages in the 1935 Stone Fort , however, are not as successful as his work in the Pine Log. His preference for the written word made his pages look cramped. To a historian, Fain’s pages are more interesting, however, because there is more description than ever before. The pictures seem to be pushed off to the sides; he did get more pages allotted to him than the size of the book would warrant. An additional observation is in order. While he gave the Basketball team the headline, “The Undisputed Champions of the Lone Star Conference,” Fain saved his most flowery words for the football team. In a dedication which he wrote for the team, Fain wrote: “To those eleven ‘IRON MEN’ who defeated Sam Houston in Huntsville on November 24th and to the coach that trained them, we sincerely dedicate this page. ... Never will be forgotten that beautiful Saturday afternoon when the perfectly conditioned ‘Jacks fought the Cocky Bearkats to a standstill and emerged victorious with a 7 to 6 verdict. ... For the first time in history, a Lumberjack team had beaten Sam Houston in Huntsville.” Victor loved the historic, heroic nature of the gridiron event; victories were expected from the basketball team.

[Victor himself was a baseball player, a second baseman. He played on a team called the Whitemen; their mentor was Coach Gene White. Later, Victor coached a team of his own, sponsored by the Dr. Pepper Company and his former Pine Log business manager John Lynn Bailey; the team was called the “Fainmen.”]

In the Spring of 1935, Victor was a student in a new, experimental course which Dean T. E. Ferguson in the English Department was offering for the first time at SFA–a course in advanced composition for journalists. The class decided it would edit “a professional edition” of the Pine Log; the aim was to offer “a paper reflective of the training we have had.” Because of Victor’s work in this course and with the subject of sports, the students elected him as editor-in-chief for the next academic year. The class project of the professional edition did not appear until near the end of the term, but the experience encouraged Professor Ferguson to offer English 371 again in the fall. In his first edition of the Pine Log as editor, Victor featured the new journalism course and stated: “It is planned to make this course a laboratory for work on The Pine Log.”

Victor’s first editorial came in this same edition. It appeared on the anniversary of the college’s opening, September 18. He traced a history of the early years at SFA. He set right the verbal trap everyone makes when referring to the opening of the doors of the college: “It must be corrected, of course, there were no “doors” to open.” That Victor would select a historical subject–a review of the past twelve years of SFA–gives us an insight into the importance he was to place always on an historical approach to understanding anything.

The editorial entitled “Twelve Years Ago!” is vintage Victor. He carefully and accurately outlined where the school had been, what it was doing at the moment, and projected proposals for its future. When he chaired the Nacogdoches City Zoning Board in the early 1970s, he proceeded with a problem in the same way. He would seek the high points, discuss the low points in passing, lay out the options at hand, and project the future with optimism and appreciation for the foundation on which the whole thing was built. He concluded his first major editorial in the Pine Log this way:

“The dreams of those courageous student enrolled twelve years ago –those visions of our beloved president and friends of the school–they shall not have been dreamed in vain. Yearly has their admirable faith been rewarded; those hardy pioneers, they blazed the trail for us, and today and tomorrow shall we honor them! And as the thirteenth act of the great drama revolves, we are grateful for the part that it is our opportunity to play!

After the turn of the new year, he reflected: “1935 was a great year at Stephen F. Austin,” one of “progress, growth and achievements–athletically and academically.” After reviewing the specifics, he then turn to 1936 with a review of upcoming projects, such as the hope for a new athletic stadium, track, woman’s dorm, home economic house, and a revamped intramural sports program for men. He ended by returning to a theme which he had occupied his thoughts in earlier editorials: “And we wish that 1936 could witness the curtailment of the student thievery and dishonesty on this campus.” While he recognized it could not be eliminated, it could be “greatly improved even with slight cooperative effort on the part of that portion of the student body which is honest.” He called a campaign led by the students: “A sense of honor must be aroused!”

Victor has always loved lists. His list for the new year in 1936 posed the question, what would make SFA a better place: sportsmanship, companionship, a sense of loyalty to school and community, accepting responsibilities, working with others through clubs, developing a clear vision, more level-headed thinking, “Or, is it all of these things together?”

While other editors wrote about noise in the halls, the problems of commuting, or apathy, Fain was worried about the lack of flexibility in the academic curriculum, in particular the “rigid recitation hour system.” He said it was behind the times and ill-suited to teaching students new and changing subjects. “Different students must be taught in different ways.” While he thought the rote system might work in language study, it was not suited to the scientific fields or history. “Actual work is becoming more and more used to teach history and social sciences. The use of many books for the preparation of papers and individual projects requiring research are making formal education change its system.”

Victor’s editorials in late January and early February are among his best. They are more confident, deeper in their thinking, and include more historical references. He frequently quoted his history professor and educational hero, President Birdwell. In an editorial entitled, “Whigs and Tories in Education,” after an expository of the whole problem of the terms in historical context, he concluded that Birdwell had the right idea in teaching them to avoid excess: “We must be Whigs, but not too liberal; we must be Tories, but not too conservative.” In another essay, he mused on the sad yet exhilarating nature of the academic calendars, the constant endings and new beginnings which repeat themselves every term. His list, as usual, called upon his readers to make the best of everything, to influence people for the good, to maintain a healthy attitude, and to worry less about things one cannot control.

The young editor made fun of the “collegiate men of the world” who were sullen in class, bored, priding themselves on their records of cuts, flunks, and excuses. He denounced their halo of cynicism, their blasé attitudes, and predicted that their attitudes would change once they left the ivory tower and were forced to “produce in order to share.” In his opinion, “one must fight for things worthwhile.” This is good copy for any generation.

1936 was a good year for people who loved history and especially Texas history. In preparation for the March 2 Centennial Celebration, Victor wrote some long editorials about the importance of the past to the present. He reviewed the deeds of the patriots, but in true form he did not forget to challenge his contemporaries to complete the tasks of keeping Texas free and independent. He published a piece which quoted the Nacogdoches poet Karle Wilson Baker to inspire the reader. His admonition to his fellow students not to accept the holiday as a matter of course, in his words, “a time when they can throw aside the cloak of study and rest or play.” The significance of the day should not be lost. Of course, the spring of 1936 was full of local as well as statewide celebrations. Locally, the movement to build a replica of the Stone Fort on campus was the big talk. Victor supported the move of the Fort to SFA.

Victor graduated in the spring of 1936. In his last essay, he wrote: “Writing down the word farewell makes a lump swell in my throat.” The year had had its troubles, but he looked back over his thirty-three issues “with a sense of price, also of disstisfaction, realizing now the mistakes that were made and the improvements that could and shold have been added. ...The one thing that I always strived to do was to make The Pine Log representative of the school as a whole.” Emotion, a difficult element to introduce into any piece, was always a hallmark of Victor’s work. He was able to make it work because it was always such a genuine emotion, and emotion mixed with good, common sense.

Fain continued actively to be interested and helpful to SFA in the immediate years thereafter. He helped to form the ex-editors club, talked to the campus press groups, and gave Assembly Programs on what it was like in the real world. In 1937, he joined the staff of The Redland Herald . He frequently, however, returned to the campus. In one of his speeches, he ended by urging the students to “cooperate in the sweat-pouring job of getting the weekly Log to press.”

“The college newspaper, to a large extent, is instrumental in forming people’s impressions of the school. A good dignified newspaper which will command respect is your job. We judge Sam Houston by its ball teams and newspaper, which may be a poor way. But regardless, we are judged in much the same fashion.”

As student editor-in-chief of The Pine Log, Victor Fain set a high standard. As editor and publisher of The Daily Sentinel. for decades, he did the same thing. Modern media leaders should take pages from both Fain’s youthful pages and his mature pages.