Several sudden flashes appear to momentarily light the sky on fire. Safe behind glass windows, cozy in his living room, Michael Tidwell ’00 watches the storm build past the distant hills near his San Antonio home. He patiently waits for morning, when he will walk outside on his back deck, collect his camera equipment and discover if he’s captured any bolts of lightning with his long exposures.

Long-exposure photography isn’t Tidwell’s day job. It’s a hobby he picked up in the early 2000s that has helped him bridge his personal life and successful career as a medicinal organic chemist.

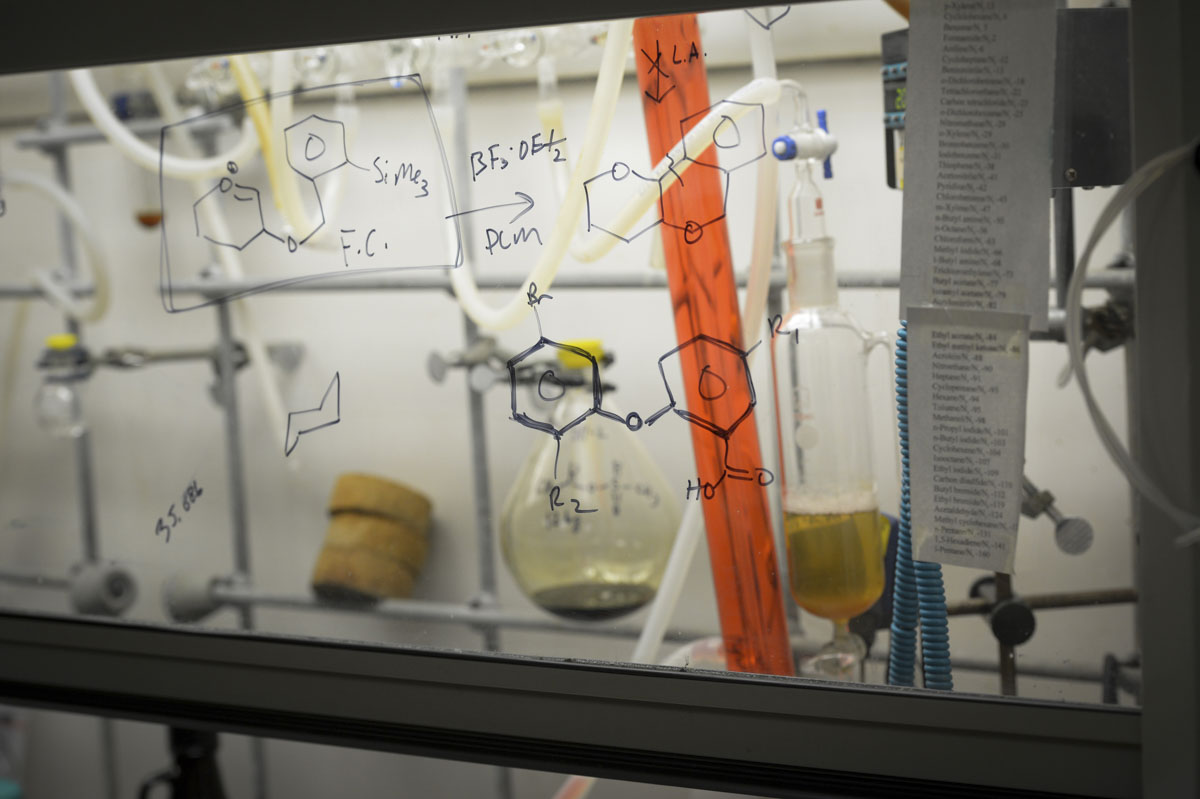

“Talking to people about the Ebola virus or nerve gas antidotes or a compound I made for Alzheimer’s — that can be a very difficult thing, especially if they don’t have the background to understand synthetic, organic chemistry, which is basically what I do,” Tidwell said while seated in his San Antonio-based office at the Southwest Research Institute, a nonprofit research and development organization. “Once you say the word ‘chemistry,’ many people can kind of shut down. With photography, that’s not the case. I am kind of an introvert, and photography is one way I can talk to someone, and sometimes I can use photography to lead into science.”

Tidwell has spent 17 years in the organic chemistry field, and, in that time, he has had a hand in the production of several potentially lifesaving compounds.

‘Very well prepared’

Though Tidwell’s interest in organic chemistry didn’t develop until his first years at SFA, his passion for scientific discovery began at a young age.

“My father has multiple sclerosis,” Tidwell explained. “That is probably the one thing that has driven me more than anything else — to one day get to a place where I can make MS drugs.”

After graduating in 1996 from Hemphill High School, Tidwell began attending SFA under the recommendation of his high school chemistry teacher and SFA alumna, Sherrill Hobbs ’86.

“After 25 years of teaching, Michael is still my favorite success story,” Hobbs said. “He came from very humble beginnings in one of the lowest socioeconomic counties in the state. Through intelligence, integrity and sheer determination, he has worked tirelessly to better himself and more importantly to make a lasting contribution to mankind through his work. To say that I am proud of him is a huge understatement. I am certain that he will continue his efforts to help mankind through his work for many years to come. I was honored to be his teacher.”

It was while studying a 45-step synthesis of cortisone in former SFA Professor Roger S. Case’s advanced organic chemistry course that Tidwell’s enthusiasm for organic chemistry was born.

“He was the first person who really showed me how organic chemistry could be used to make new drugs,” Tidwell said. “I also was an organic lab teaching assistant for Dr. James Garrett. He taught organic chemistry at SFA much longer than Dr. Case, but he was not doing research during my time there. However, Dr. Garrett is certainly the person who influenced me to apply to work at Eli Lilly and Company.”

With a bachelor’s degree from SFA under his belt, Tidwell moved to Beaumont to attend Lamar University, where he received his Master of Science in chemistry in 2002 and completed a thesis on new synthetic methods for C-Aryl glycosides, an important class of natural products.

From there, he applied to three companies and was offered a position at each. He accepted one, and from 2003 to 2009, Tidwell synthesized more than 600 target compounds for Eli Lilly, a global pharmaceutical company headquartered in Indianapolis. He and his family returned to Texas when he joined the SwRI team in 2009.

“I think those successes show that I not only had an excellent teacher in high school, but that I was very well prepared by the chemistry department at SFA,” he said.

Lifesaving compounds

On March 25, 2014, the World Health Organization reported an outbreak of the Ebola virus in four Southeastern districts in the African country of Guinea.

For some time, Tidwell had been interested in studying neglected tropical diseases — or those often-fatal diseases many pharmaceutical companies decline to research because of their rarity, he explained.

Contacting a scientist from SwRI’s sister company, Texas Biomedical Research Institute, where his wife, Tammi, works, Tidwell began creating and testing compounds to combat the neglected tropical disease sweeping across the African continent.

“They have a BSL (biosafety level) 4 lab where they can work with the Ebola virus,” Tidwell said. “I was looking for ways to work with neglected tropical diseases, so I found the one scientist there who was working with small molecules. I contacted him in 2014 and told him about our capabilities. He asked that I make a compound that he could no longer buy, and, in making that compound, we were put into a scientific publication as co-authors.”

On Feb. 27, 2015, the team’s successful results were published in the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s magazine Science, one of the most prestigious publications for scientific discovery.

While it would be difficult to say his team found a “cure” for Ebola, it is making meaningful progress in optimizing its compound. His team is producing new compounds that are now more potent than the natural product on which they are based.

“The drug-discovery process is immense,” Tidwell said. “One person does not make a drug. It’s a huge team. Think of it like this: When I was in the (pharmaceutical) industry, I had at least four different projects reach a candidate-selection phase. Those (drugs) still probably have 10 years or more before they will be put on the shelf. That’s why I can’t come in here and say ‘I made this or that drug.’ But I can say that I have contributed to eight patents and several publications in peer-reviewed journals in the area of medicinal chemistry.”

What Tidwell can know is that compounds developed in his lab at SwRI have the real potential to save lives. One example, he said, is a compound he synthesized for the U.S. military that serves as an antidote to nerve gases.

“SwRI is highly regarded for producing some of the best nerve gas antidotes in the world ... and that is something I really feel good about,” Tidwell said. “Because five years from now, there could be a soldier in Afghanistan or Iraq who could be exposed to a deadly nerve agent, and he or she could pull an auto-injector from his or her bag and inject an actual molecule that we discovered right here at SwRI.”

Fulfilling his passions

To say Tidwell is doing exactly what he envisioned as a young boy would be putting it mildly.

“I would say this is probably more than exactly what I wanted to do — to work on infectious, neglected diseases,” he said. “Just the idea that I can chart my own course here is wonderful. For example, my mom was recently diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. I saw her go downhill pretty quick. So just to know that you have the power, the department, the knowledge, and you are able to help in a real way, I just can’t really stress enough how that feels.

“Based on things I’ve done — different publications, different patents — someone someday down the road may need a certain type of reaction, and they could look on the computer, find a reaction I’ve worked on, go into a lab and one day possibly use something I’ve worked on to make a cancer drug. So as far as doing what I want, I’m as happy here as I could ever be.”

With all his career successes, Tidwell is sure to pursue his love of photography in his spare time, using it as a tool to connect his personal and professional life.

Photographs he has taken have been purchased and reproduced by SwRI administrators and are scattered across the 1,200-acre research campus. He was recently honored to produce several canvas prints for a special display at the residence of the SwRI president. He continues to experiment with exposure times and locations and hopes to capture a lightning storm against a backdrop of the San Antonio skyline by the end of the year.